The Evolution of Home Computing: A Journey Back to the Birth of Personal Computers

Revisiting the Evolution of Consoles and Home Computers: A Nostalgic Journey through 1980s Technology

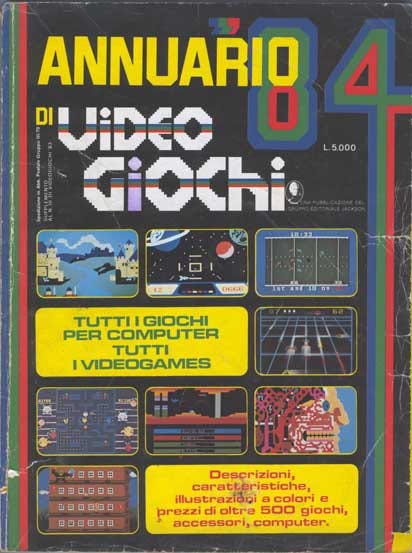

“Once upon a time”, there was a time when the term Personal Computer had no meaning. It was the era of consoles, small gadgets that connected to the TV, the precursors of today’s Playstations. The magazines of that time showcased a variety of consoles: Intellivision, Atari, Philips, large machines — for that era — that promised entertainment combined with amazement. The early magazines, like the 1984 Video Games yearbook

introduced advertisements that displayed groundbreaking technology never seen before. For instance, the Colecovision, with its Video Game System, was advertised as “a home console for video games on standard Colecovision cartridges,” at the exceptional price of 485,000 Lire (~ $300,00).

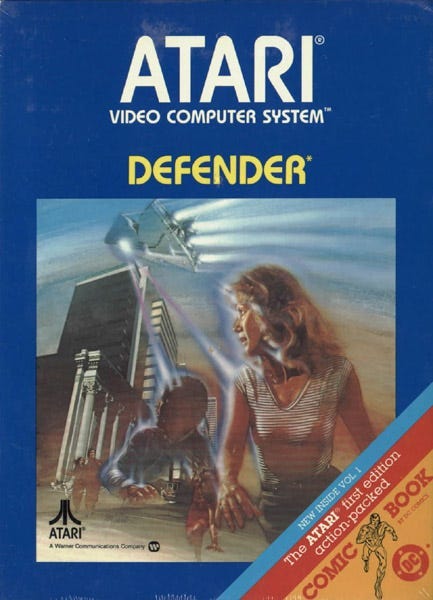

The Atari, with its System 2600 allureingly portrayed as “perhaps!” in ads, came at a slightly lower cost of 299,000 Lire (~ €190,00). Like its console counterparts, it hooked up directly to the TV, offering the enticing bonus of the game cartridge, Defender!

Philips stepped into the limelight with the Videopac Computer G 7200, showcasing an integrated 9" black and white monitor, embodying the essence of a “portable” device of the 1984 era.

This system could also operate on a regular color TV. Though the games were limited, seeing those 4 colors even in black and white was quite impressive. Nevertheless, the concept was excellent.

One of the best-selling consoles of that time, at least as I recall, was the Intellivision, priced at 399,000 Lire.

Its strengths included the abundance of available games and the innovative control system used in the joysticks. However, there is always something that sells more, seemingly without a genuine reason, as if fate randomly chooses a lucky one for a better destiny.

Looking back at those old magazines, one striking observation is the scarcity of “technical propaganda” accompanying the advertisements. There was no boasting about the number of colors, CPU speeds, memory; no mention of anything that could potentially confuse the reader, a prospective buyer. The prevalent terminology used today was not yet pervasive. The focus was on using impactful words resembling Italian, such as vision, video, system, and so forth.

The arsenal of the Colecovision was my favorite.

Notice the included headphone modem. It was truly comprehensive with its monitor, and printer. Who, in those times, didn’t dream of having it?! Costing 415,000 Lire, it also boasted a serial-parallel interface and a cassette recorder! Unbelievable.

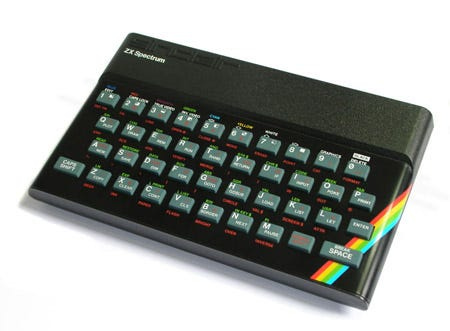

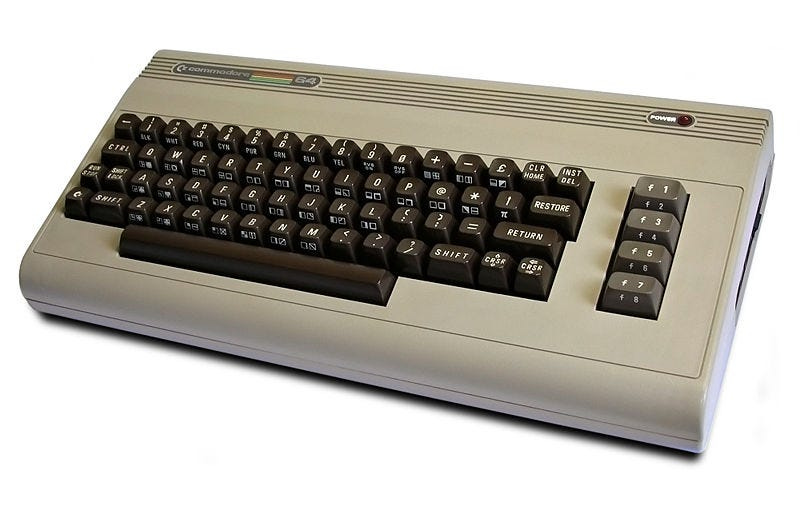

The real battle was between two computing gems of that era: the Commodore 64 and the Sinclair Spectrum.

These two giants dominated the scene between late 1983 and 1985, while the more professional Personal Computers were fine-tuning their MS-DOS.

The clash between them was fierce. Soon, two factions emerged: the Spectrum enthusiasts and the Commodore supporters! Each fervently stood by their choice. Ultimately, as history tells us, the C64 prevailed, despite the undeniable quality of Sinclair’s product. Just like the ongoing rivalry between PC/Microsoft and Apple, the reasons for one’s victory over the other remain somewhat elusive, except that it had to happen in some way.

Surprisingly, one of the proponents of expanding and popularizing the concept of Home Computers, and later Personal Computers, was the Texas Instruments’ TI99, a forerunner of the C64 and Spectrum.

I remember seeing a TI99 for the first time on a television show, explaining that Computers — the Home Computers — were the future because, unlike consoles promising only games, they could perform numerous other functions, including being programmable.

The show demonstrated how easy it was to design and create a simple Video Game or use the Computer as a powerful calculator. Despite this push, consoles did not fade from the market. A dedicated machine certainly offered superior performance compared to any PC, no matter how “upgraded” it might be. However, this perception might not hold true anymore!

Even back then, the so-called Bar consoles offered incredibly detailed graphics and animations. I remember spending hours admiring those magnificent works, crafted from pixels and mysterious codes. It was a challenge to replicate those effects on a home Computer, so it was fascinating to find interviews and photos of game developers, peek into their studios, and try to understand the hardware they used to create “Bar games.”

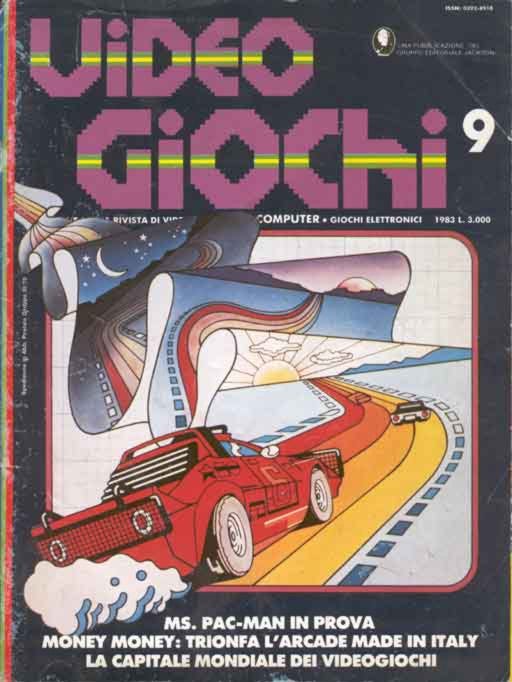

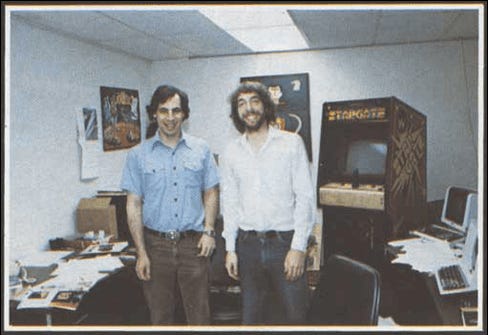

During that time, the Jackson Editorial Group dominated the newsstands. Many computer magazines bore their mark, before the competition diminished their exclusivity — no offense intended! In fact, we owe these editorial groups the credit for the “computerization” dissemination of those years. Of particular interest in this publication was an exclusive interview. The editorial team of Video Games went to North Halsted, Chicago, to visit a software house led by Eugene Jarvis, the creator of Defender, Stargate, and Robotron.

Here, Jarvis had founded his “small” company, Vid Kidz, where he happily worked on his projects.

Having graduated in computer science and electronic engineering in 1977 from the University of Berkeley, Jarvis briefly worked at Hewlett-Packard for three days before resigning. “The main issue,” explained Jarvis,

“is working in a large company. When you are doing creative work, you don’t want to seek permission every time you need to do something.”

Clearly, even at that time, corporate structures were evidently stifling the creativity and peace of mind of developers. Jarvis then moved to Atari, focusing on pinball machines. Unfortunately, the pinball section was closed down — a harbinger of the new era of computing. When the first video games arrived in American homes between 1977 and 1979, Jarvis was immediately captivated and began playing them.

“I used to be an old pinball player […] but suddenly, I started playing only video games. I considered them the best games around. That’s when I decided I wanted to make one myself!”

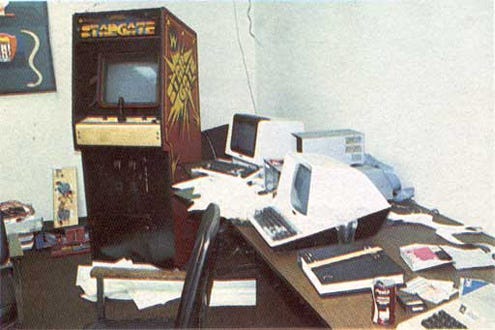

And so, in February 1980, the development of Defender began, a classic game. With its 24K of memory, 16 colors, sound generated by the 6800 sound chip, 6809 microprocessor, and horizontal scrolling with parallax effects, it was truly a spectacle for that time. As we continue exploring Jarvis’s studio, we admire his workspace. A standout piece is the P 6809 system on the table, alongside a 20 Megabyte Winchester disk and two 5 ¼" floppies with a maximum capacity of 700Kbytes! The P 6809 is highlighted by Jarvis as

“the most advanced 8-bit microprocessor on the market. It works fine, although the next generation of video games will likely use 16-bit chips.”

The development language inevitably was Assembly.

“We use this language to leverage its speed. It might be easier to write a game in Basic or Pascal, for example, but with Assembly, the program runs faster, making our 6809 resemble an IBM P70.”

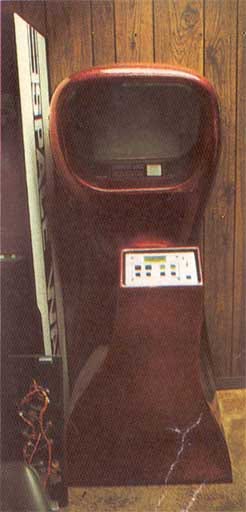

In the original interview, Jarvis chuckles at this point, and we can only join him in this visionary statement. At the Creator of Defender’s headquarters, we can also behold Computer Space, the first bar video game in history.

Indeed, much water has flowed under the bridge since those times. Technological advancements of recent years have made us forget how programming was once done. Standard development tools like today were nonexistent.

“We develop everything ourselves because we want to understand every step, and because we have high-quality standards. When you create a game, you have to write it yourself.”

Who can disagree with him?

Quality seems to be inversely proportional to technological progress and not just in computing, evidently. Assembly programming and an in-depth knowledge of the hardware on which one works are gradually vanishing from the cultural heritage of “new developers.”

Those like me, who lived and continue to live by that “development style,” would gladly trade today’s gigahertz for yesterday’s 2 MHz P 6809. I believe nothing today compares to the results achieved in those years.